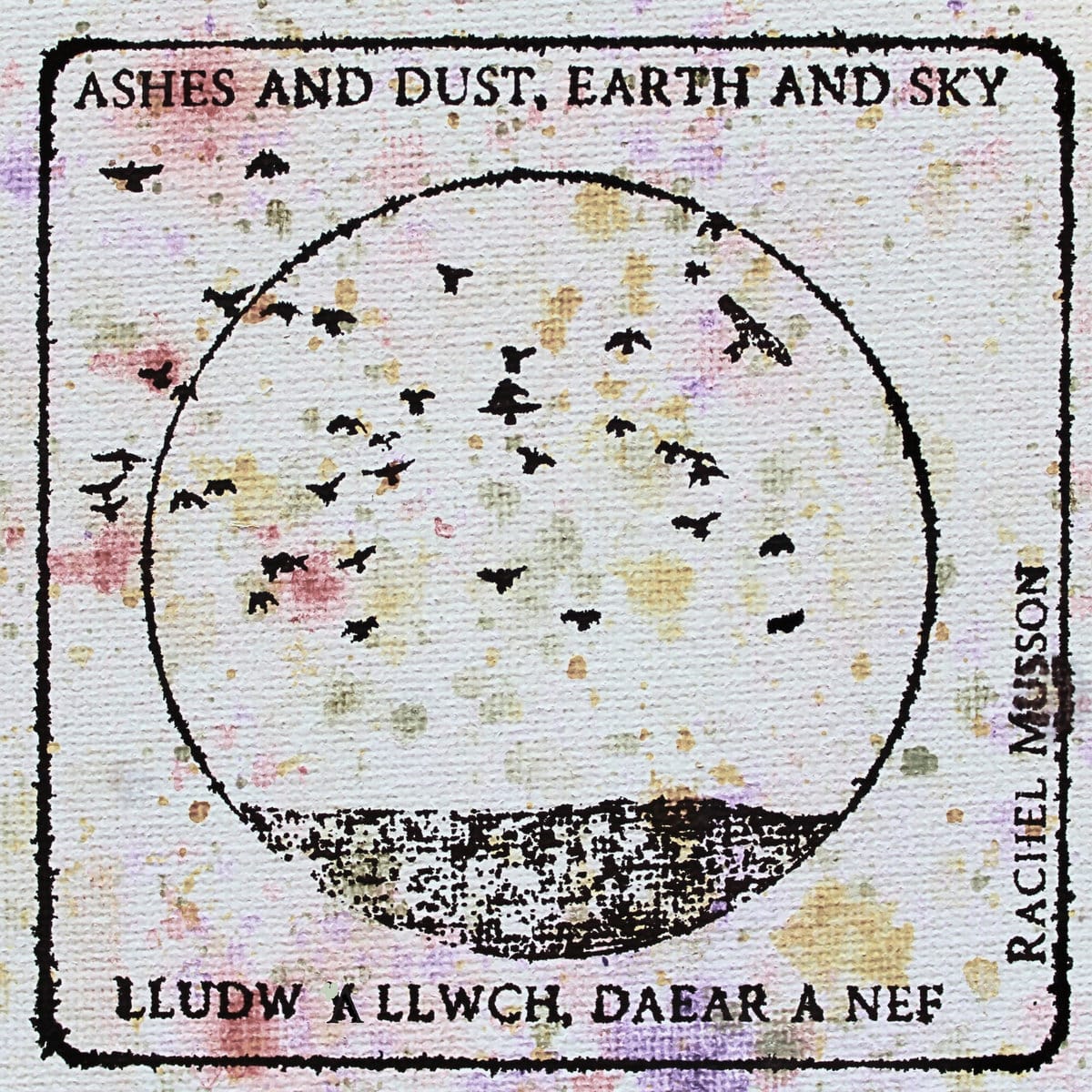

Review: Rachel Musson – Ashes and Dust, Earth and Sky, LLudw a Llwch, Daear a Nef

Portals between the city and West Wales for saxophone, flutes, field recordings and other materials.

Musson isn’t mimicking the birds. Her flute sings with them in simultaneity. On the album's first track, the instrument is set back inside the field recording, tucked behind the trickle of liquid (presumably the “Meltwater” of the track’s title) and joining the birds in descendent trills and swoops. Clearly she has been here before. Perhaps she’s played this field recording over and over, learning it in the manner that one might learn a score. Or perhaps she’s learned the daily rituals of the place itself, entwining herself with its happenings and inclinations, now capable of anticipating each habitual vocalisation from its creatures. Eventually, flute is joined on "Meltwater" by other guests: further flutes to form a scattered flock, and the low hum of what appears to be a singing bowl hung from the base of the landscape. Suddenly, the field recording stops. There’s a brief flurry of woodwind confusion before the track concludes. Where did the birds go?

In an accompanying description, Musson talks about yearning for “open skies and air and sea” from her home in London. Specifically she yearns for West Wales, where her ancestral family lived and worked for generations. While the album features field recordings derived during her own trip to West Wales and the Gwaun Valley, this location primarily manifests as something imagined. The landscape is held in the minds eye, romanticised and longed-for, perpetually at risk of shattering as the reality of the city forces itself back in. Take the first half of “Dawnsing”, whose edgeless pooling of hums and saxophone resonances feel like a daydream mid-melting, or a hung tapestry slipping off one side of the wall. The acoustics are integral here. Sometimes they tell us that we are unequivocally trapped inside, such as the abrupt echo adorning the voice/sax/breath improvisations on “Keystone”. Yet occasionally the walls come down, as in the flutes spiralling across the latter half of “Dawnsing”, ridden of acoustic reflections, relishing their liberation into the outdoors.

Other than flutes and saxophones, metallic resonances are the other recurring presence. Chimes, singing bowls. They feel like portals; magic doors between the cramped state of pandemic living and the unfurled green of the Gwaun Valley. Perhaps there’s a literal component to this. Tools associated with meditation and inward focus are used to bring these imagined landscapes to greater clarity and brighter colours. Yet the church bells of the last track kick up another possibility: that these chimes are miniature, almost prophetic evocations of this final field recording, with flutes and birds dancing beneath the cascade of the bell tower. Inevitably, the image melts. The bells fall into distorted half-time, while the sounds of nature find their domestic dream-instigation twins: meltwater becomes the trickle of a dripping tap, the buzz of summer bees becomes an irate whirr akin to a boiler in winter. We are, for better or worse, back home again.

![Review: [something's happening] – Buzz](/content/images/size/w720/2025/03/a3798122591_10.jpg)